Traducción del Editorial “No turning back ” publicado en la revista científica Nature el 12 de noviembre de 2009

(Tomado de La comunidad. Apuntes científicos desde el M.I.T. )

Nature 462, 137-138 (12 November 2009) doi:10.1038/462137b;

Published online 11 November 2009

Sin vuelta atrás

España no debería utilizar la recesión como excusa para paralizar los planes de impulsar su actividad científica.

En las últimas dos décadas España ha pasado de ser un desierto científico a convertirse en un jugador respetado internacionalmente en el mundo de la investigación. Gran parte de ese progreso se ha producido desde que el Partido Socialista llegó al poder en 2004, comprometiéndose a convertir a España en una economía basada en la innovación (véase Nature 451, 1029, 2008).

Durante el primer mandato socialista, por ejemplo, se duplicó el presupuesto para la ciencia hasta superar los 8 mil millones de euros, situándolo por encima del 1,1% del producto interior bruto del país (PIB) y mucho más cerca de la media de la Unión Europea (1,8% del PIB). El partido socialista fue reelegido en 2008, habiéndose comprometido a reducir la burocracia e impulsar la financiación de la investigación hasta alcanzar el 2% del PIB. Casi de inmediato se constituyó el Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, extrayendo finalmente la ciencia de las competencias del Ministerio de Educación. Cristina Garmendia, una bióloga molecular que ha fundado varias empresas biotecnológicas de éxito, fue nombrada responsable del nuevo ministerio.

Desde entonces, sin embargo, se ha perdido impulso. La inexperiencia política de Garmendia ha quedado demostrada. Fue lenta en poner el ministerio en funcionamiento, y no ha desarrollado la influencia política necesaria para convencer al gobierno, ahora lidiando con la recesión global, en mantener su visión para la ciencia.

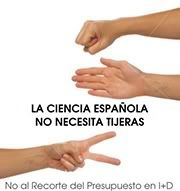

El gobierno ha reforzado el apoyo financiero para las industrias de alta tecnología y biotecnológicas. Pero su propuesta de presupuesto para 2010, que dio a conocer en septiembre, significa un recorte del 45% para la financiación directa de la investigación básica. La protesta de la comunidad científica logró reducir el recorte al 15%, y durante los debates parlamentarios es probable que se añada un extra del 2,8% para el ministerio de ciencia. Pero esto todavía sería un duro golpe a la investigación del país.

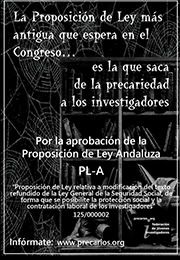

Mientras tanto, el gobierno todavía debe preparar su tan anunciada ley de la ciencia. Se suponía que iba a crear una agencia de financiación independiente y reformar el sistema tan inflexible de reclutamiento académico del país, bajo el cual los profesores universitarios y científicos del gobierno son funcionarios públicos con derecho automático a un empleo hasta la jubilación. Se han establecido fechas de presentación de la ley en el Parlamento y después han sido retiradas, al parecer porque algunos sectores del gobierno no quiere excluir a los científicos de las normas que se aplican a otros empleados gubernamentales. La contratación de nuevos investigadores continúa siendo un proceso difícil y lento, y es casi imposible ofrecer un paquete de salarios y dinero para investigación competitivos. El ministerio de ciencia ahora dice que la reforma de la ley será presentada al Parlamento antes de finalizar el año, pero la comunidad científica está perdiendo la fe en que esto suceda.

En el largo plazo, la industria estará pobremente apoyada debido a la falta de una investigación básica fuerte. España se equivoca al seguir la noción simplista y obsoleta de que un país puede vivir de transferir conocimiento, si al mismo tiempo se detiene la generación de conocimiento. Esta no es una forma inteligente de responder a la crisis financiera.

España haría mucho mejor si emulara los compromisos asumidos el mes pasado por otras dos naciones europeas, que también están batallando contra la recesión económica. En Alemania, un país rico con una economía casi estancada, el gobierno de centro-derecha está recortando el gasto público para 2010 en todas partes excepto en investigación y educación, a las que está dando aumentos enormes (véase Nature 462, 24, 2009). En Grecia, un país pobre con una economía en recesión, el gobierno de centro-izquierda dice que también reducirá el gasto público para 2010 en todas partes excepto en investigación y la educación, a las que está otorgando incrementos modestos. Los gobiernos de ambos países también planean eliminar algunos de los trámites burocráticos que limitan la investigación.

España disfrutó de un gran período de esplendor intelectual a comienzos del siglo XIX, conocido como su Edad de Plata. Hasta hace poco, los científicos españoles se mostraban optimistas pensando que avanzaban hacia una segunda Edad de Plata. Ahora bromean diciendo que España se dirige hacia una Edad de Bronce. Pero no se ríen.

Original Version

Original VersionNature 462, 137-138 (12 November 2009) doi:10.1038/462137b;

Published online 11 November 2009

No turning back

Spain should not use the recession as an excuse to stall plans to boost its scientific enterprise.

The past two decades have seen Spain transform itself from a scientific backwater into an internationally respected player in the research world. Much of that progress has occurred since the Socialist Party swept to power in 2004, pledging to turn Spain into an innovation economy (see Nature 451, 1029; 2008).

During the Socialists' first term in office, for example, they doubled the science budget to just over 8 billion (US$12 billion), pushing it above 1.1% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and much closer to the European Union average of 1.8% of GDP. The party was re-elected in 2008, having pledged to cut bureaucracy and push funding for research to a target of 2% of GDP. Almost immediately it set up the Ministry of Science and Innovation, finally extracting science from under the purview of the education ministry. Cristina Garmendia, a molecular biologist who has founded several successful biotechnology companies, was appointed as head of the new ministry.

Since then, however, the momentum has been lost. Garmendia's political inexperience has shown. She was slow to build up a functioning ministry, and has not developed the necessary political clout to convince the government, now grappling with the global recession, to stick to its vision for science.

Granted, the government has bolstered financial support for the country's budding biotechnology and other high-tech industries. But its draft budget for 2010, unveiled in September, proposed a cut of 45% for directly funded basic research. An outcry from the research community reduced that cut to 15%, and an extra 2.8% top-up for the science ministry is likely to emerge during parliamentary discussions. But this would still be a heavy blow to the country's research base.

Meanwhile, the government has yet to produce its much-heralded law for science. This was supposed to create an independent granting agency and reform the country's inflexible system of academic recruitment, under which university professors and government scientists are civil servants with an automatic right to employment until they retire. Dates for the law to be presented to parliament have been set and then withdrawn, apparently because some parts of the government do not want to exclude scientists from rules that apply to other government employees. Hiring new researchers continues to be a difficult and slow process, and it is almost impossible to offer a competitive package of salary and research money. The science ministry now says that the reform law will be presented to parliament before the end of the year, but the research community is losing faith that this will happen.

In the long-term, industry will be poorly served by a failure to develop and maintain a strong basic-research base. Spain is ill-advised to wed itself to the simplistic and outdated notion that a country can live on transferring knowledge while running down the knowledge generator. This is not a wise way to respond to the financial crisis.

Spain would do far better to emulate the commitments made last month by two other European nations as they too wrestle with the economic downturn. In Germany, a rich country with a near-stagnant economy, the centre-right government is cutting back public expenditure for 2010 everywhere except research and education, to which it is giving huge increases (see Nature 462, 24; 2009). In Greece, a poor country with an economy in recession, the centre-left government says it will likewise cut public expenditure for 2010 everywhere except research and education, to which it is giving modest increases. The governments in both countries also plan to remove some of the red tape that restricts research.

Spain enjoyed one great period of intellectual brilliance in the early nineteenth century, referred to as its Silver Age. Until recently, Spanish scientists were optimistic that they were on their way to a second Silver Age. Now they joke that Spain is heading towards a Bronze Age. But they're not laughing.

It is relevant to add a comment about the transparency in distribution of money. In Spain the criteria of good and bad science is the "numbers" and "quality indexes". Usually there is no human evaluation. Thus, the "efficiency" should start with a clear and transparent criterios and human evaluation of scientific results. See more at http://icrea-leaks.softmat.net/suggestions/

ResponderEliminar